Search websites, locations, and people

ABOUT

ACADEMICS

RESEARCH

ADMISSIONS

NEWS & EVENTS

CAMPUS LIFE

INNOVATION

CAREERS

Mechanobiology: Westlake x Science Joint Online Symposium #8

03, 2023

Email: zhangchi@westlake.edu.cn

Phone: +86-(0)571-86886861

Office of Public Affairs

On July 27, 2023, the eighth part of our live, online symposium series jointly organized by Science/AAAS and Westlake University, entitled "Mechanobiology: A New Perspective into Cellular Physiology, Development, and Diseases" was successfully broadcast to a global audience of 30,000.

World-renowned researchers Dr. Jan Lammerding (Cornell University), Dr. Jody Rosenblatt (Kings College London), and Dr. Valerie M. Weaver (UCSF) divulged and discussed at length their research, latest insights in mechano-sensing and cellular responses to the environment during metastasis and maintaining normal cell functions. The symposium was co-chaired by Dr. Zhenjie Xu[GW1] (Westlake University) and Dr. Stella Hurtley (Science/AAAS), who facilitated the discussions and provided greater depth to the dialogue and Q&A sections.

The online symposium series promotes a platform for open dialogue and a discussion of topics and cutting-edge ideas. Global audience members comprised of fellow researchers, academics, scientists, and students from universities, hospitals, scientific research institutions, and pharmaceutical companies, who were actively encouraged to submit their questions and ideas surrounding the future directions of the research field to the speakers.

Research Highlights

Mechano-sensing and -response to the environment are essential for cells to adapt to environmental changes, such as migrating through a confined space where they have to deform their shape and nuclei, and maintaining normal cell functions, such as epithelial cells responding to the mechanical property changes in the process of breathing. Other mechano-responses provoked by inflammation and tumors on the surrounding tissues were also revealed.

Dr. Jan Lammerding, Professor in the Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering and the Weill Institute for Cell and Molecular Biology at Cornell University, opened the symposium with his talk on 'Squish and squeeze: nuclear mechanobiology in physiology and disease.'

Dr. Lammerding’s lab is one of the pioneers in nuclear mechanobiology in investigating how the mechanical property of the nucleus modulates cellular functions and how physical forces acting on the nucleus affect cellular processes.

The nucleus is tightly connected and integrated in the cell. Lamina is a dense protein network that aligns with the nucleus' inner membrane, providing stability to the nucleus. The nucleus and nuclear lamina are connected to the cytoskeleton, extracellular matrix, and cell-to-cell junctions through the LINC complex (Nesprin and SUN proteins). Hence, the nucleus can sense external forces through the cytoskeleton and LINC complex. The nucleus is the largest and stiffest organelle in most cells. Especially in cancer cells, the nucleus is enlarged and takes up most of the features of the cell. AFM and micropipette aspiration measurement determined the nucleus to be about two to ten times stiffer than the surrounding cytoskeleton. Nuclear mechanics are determined mostly by the elastic nuclear lamina and the viscoelastic nuclear interior. The nuclear lamina is the most elastic substance that binds to chromatins and performs transcription regulations. Nuclear deformability is determined by Lamin proteins.

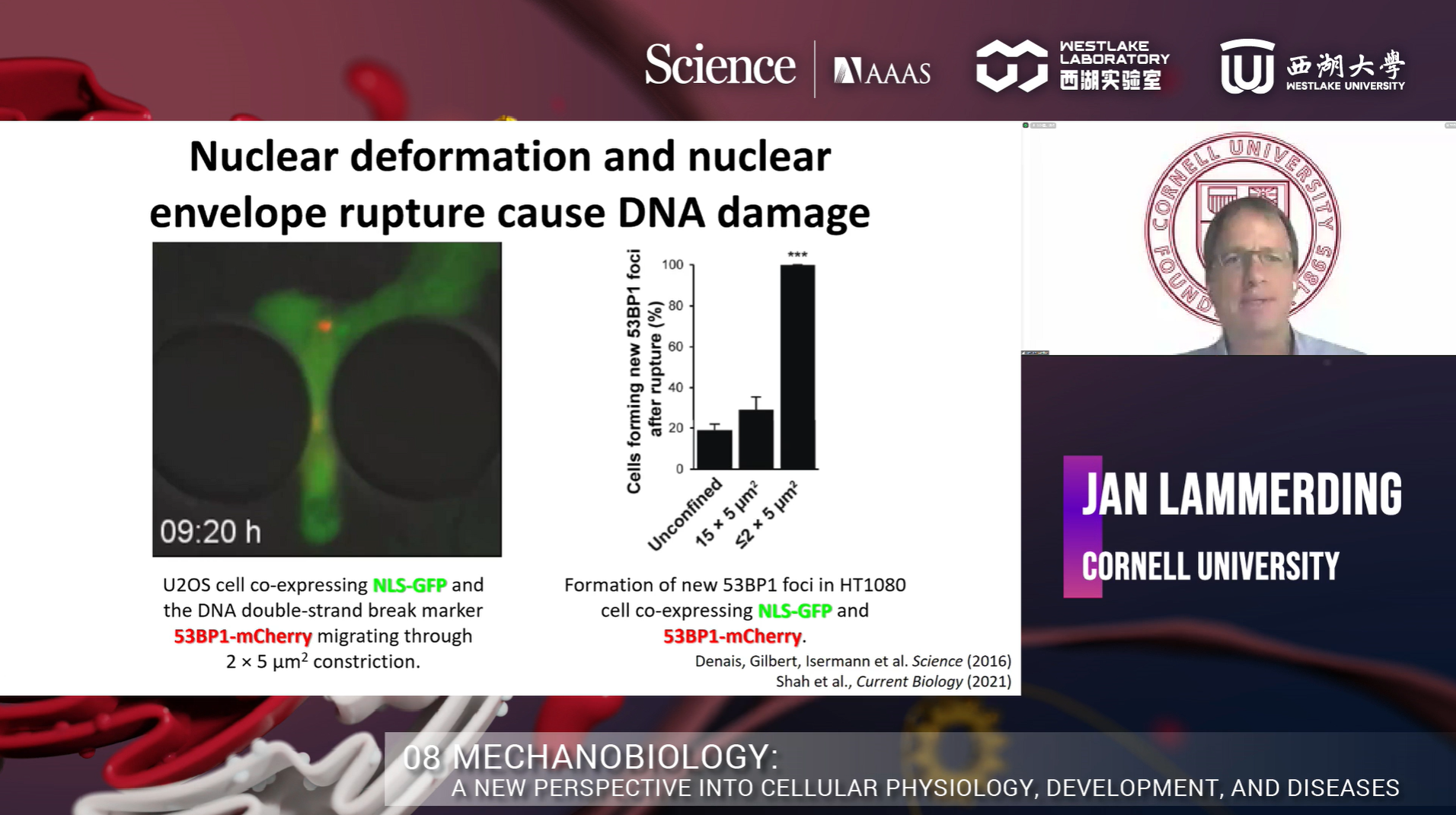

Metastasis is responsible for more than 80% of all cancer deaths. During cancer cell migration or invasion, cells undergo substantial cell deformation when they must squeeze through tight interstitial spaces much smaller than the nucleus. Dr. Lammerding and the team had observed cancer cell nuclear deformation in collagen matrix that mimicked in vivo confined environment. However, this system is very heterogeneous and difficult to visualize. Therefore, they designed a microfluidic system using PDMS to have precise control over the confinement between 2-15um. They found that nuclear deformation is a rate-limiting factor for migration through tight spaces. Dr. Lammerding’s team asked whether highly migratory cells, such as metastatic cancer cells, have more deformable nuclei. In order to test that hypothesis, they developed a microfluidic device that allowed them to trap one cell in each channel and observe nuclear deformation. They found that the highly aggressive cancer cell lines showed higher nuclear deformation compared to less aggressive cancer cell lines. When they compared the Lamin A level among those cell lines, they found that the highly aggressive cancer cell lines had lower levels of Lamin A expression. Overexpression of ectopic Lamin A slowed down MDA-MB-231 migration in confined constrictions. To investigate what other proteins may have changed after Lamin A overexpression, Dr. Lammerding’s team performed a MS study using the unmodified and Lamin A overexpressed (2-fold) BT549 cell lines. They found that 90% of the proteins in the Lamin A overexpressed cell line had changed. Most are related to metabolism, adhesion and migration, extracellular environment, transcription factors, and cellular responses. After that, they asked whether they could detect altered Lamin levels in patient samples and do changes correlate with disease progression. Their collaboration with Paul Span, Radboud University Nijmegan medical center, found that low Lamin A levels correlated with reduced disease-free survival. They further interrogated this result by performing the microfluidic confinement experiment and found that nuclear deformation and nuclear envelope rupture cause DNA damage and the increase of heterochromatin markers H3K9me3 and H3K27me3. Further study revealed that the formation of heterochromatin promotes tumor cell migration.

For the second part of Dr. Lammerding's talk, he focused on how mutations in nuclear envelope proteins can result in muscular dystrophy and what role mechanobiology plays in that process. Mutations in the LMNA gene cause muscular dystrophy, cardiomyopathy, and several other human diseases. Do Lamin mutations that cause striated muscle disease impair nuclear stability and result in force-induced nuclear damage? They generated mutant mice and isolated undifferentiated primary myoblast to investigate the effect of LMNA mutations on myonuclei in vitro. They then assessed the deformability of nuclei using their microfluidic system, and showed that the LMNA mutant myoblasts have reduced nuclear stability that correlates with disease severity. The differentiated LMNA mutant myofibers exhibited nuclear blebs, chromatin protrusions, and tethers. They also observed that the Lamin A/C deficient myotubes exhibited progressive nuclear envelope rupture. Can LINC complex disruption improve the viability and function of LMNA KO myofibers? Their study showed that LINC complex disruption rescued nuclear ruptures and cell viability in LMNA KO myofibers. In addition, in vivo examination showed that cardiac-specific LINC complex disruption improves survival in cardiac-specific LMNA deleted mice.

To conclude, Dr. Lammerding explained that Lamins A/C provides mechanical stability to the nucleus, mechanical stress on the nucleus can result in nuclear envelope rupture, physical stress on the nucleus result in chromatin modifications, DNA damage, and activation of DNA damage and cytosolic DNA sensing pathways. These mechanisms could contribute to genomic instability in metastatic cancer cells and progressive muscle wasting in laminopathies.

The next speaker, Dr. Jody Rosenblatt, Professor of Cell Biology in the Faculty of Life Sciences and Medicine, School of Basic & Medical Biosciences and School of Cancer & Pharmaceutical Sciences at Kings College London, discussed ‘Asthma: Putting the Squeeze on the Airway epithelial barrier.'

Dr. Rosenblatt discovered epithelial cell extrusion, a process that eliminates dying cells without forming any gaps, and wondered what links cell division and death together to maintain constant cell numbers. Epithelial cells are linked to each other through tight junctions. The lack of cell extrusion will cause tumor formation, while excessive extrusion will lead to asthma attacks. Crowding-induced extrusion drives most epithelial cell death. Cell extrusion is regulated by the Sphingosine I-phosphate (SIP). SIP gets secreted, binds to SIP2 on the GPCR, and activates Pho and Rac. Dr. Rosenblatt and team hypothesized this might be the initiation of metastasis, so her team utilized a zebrafish model to investigate the SIP signaling pathway. They found that Kras mutation drove mass formation and invasion at different sites, and all invading cells lacked E-cadherin. However, most invading cells die unless they also lack p53. What affects the fates of cells? Transformed cells and nuclei sustain strain during migration. They found that mesenchymal cell types increased as matrix pressure increased. From what they have found, they wonder if there could be new approaches to diagnose and treat invading transformed cells to prevent metastatic disease.

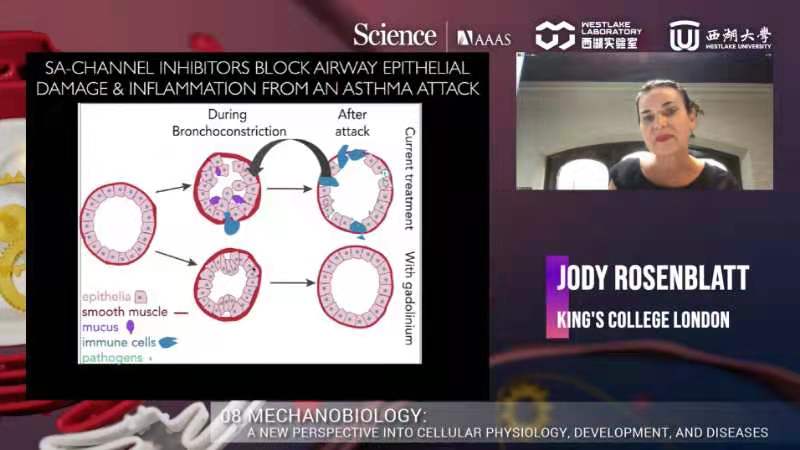

On the other hand, Dr. Rosenblatt wondered can too much crowding cause excess extrusion during asthma. They treated mice with methacholine to induce bronchoconstriction in mouse ex vivo lung slices. Bronchoconstriction (asthma attack) causes excessive airway epithelial extrusion. Albuterol, a drug to treat asthma, did not block epithelial extrusion and destruction. Therefore, Dr. Rosenblatt and the team tried different inhibitors of crowding-induced extrusion to find a way to block cell extrusion. They found that Extrusion inhibitors prevented airway epithelial destruction, and using Gadolinium to block piezo in the earlier extrusion pathway seems better to rescue the defect. Gadolinium does not impede albuterol, but prevents denuding. They confirmed that using Gadolinium to prevent cell extrusion also worked in live mice.

Furthermore, extrusion inhibitors blocked inflammation after the methacholine challenge and preserved the epithelial layer event 24 hours post-treatment. Mucus plugs are a serious problem in fatal asthma, and bronchoconstriction causes mucus secretion. Gadolinium also blocked the secretion of mucus in vivo. In upcoming research plans, Dr. Rosenblatt wanted to investigate whether they could prevent asthma attacks in humans.

The last speaker, Dr. Valerie M Weaver, Professor and Director of the Center for Bioengineering and Tissue Regeneration and Co-Director of the Bay Area Center for Physical Sciences and Oncology at UCSF, gave an insight into the ‘Interplay between inflammation, anti-tumor immunity, and tissue tension.'

Fibrosis and ECM stiffness are associated with collagen crosslinking in breast tumors. Collagen crosslinking enzymes are increased and associated with poor prognosis in human breast cancer. Dr. Weaver and the team found that preventing ECM stiffening reduced malignancy and tumor progression. Dr. Weaver's lab primarily looked at integrin signaling as aggressive tumors have higher levels of activated β1 integrin. High tension potentiates focal adhesion, integrin singling, and so on. Lysyl oxidase (LOX) is involved in ECM stiffening. Thereby, using LOX inhibitor for blocking lysyl oxidase activity reduced circulating tumor cells, lung metastases, and decreased tumor grading. Moreover, they also see the reduction of EMT markers, such as vimentin, Zeb1, Snail1, and Slug. They isolated tumor cells from these mice, transplanted them into ECM with different stiffness, and found an increase of phospho-ERK (Extracellular signal-regulated kinase) and phospho-FAK (Focal adhesion kinase), increasing integrin. RNAseq results revealed the increase of ECM signaling and EMT markers in a stiffening environment.

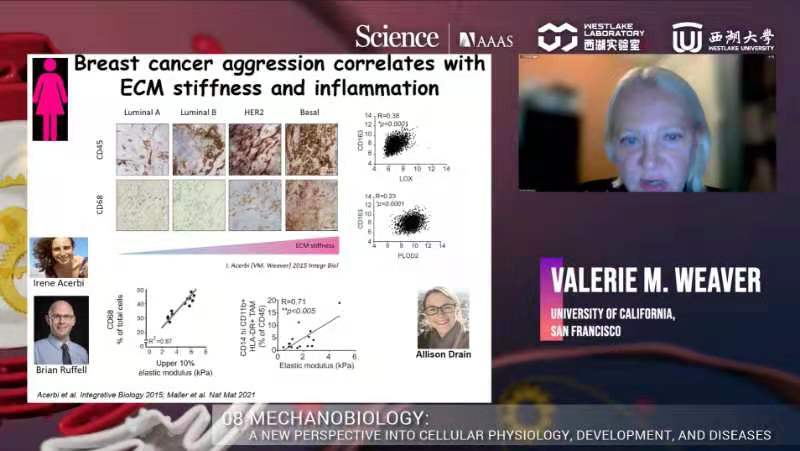

Then, Dr. Weaver asked what drives the stiffening. They interrogated different phenotypes of breast cancer, and found a myeloid cell marker, CD68, increases as ECM stiffness increases, indicating that breast cancer aggression correlates with ECM stiffness and inflammation. They block early macrophage in mouse models using alpha-CSF1 antibody, and that reduces tumor metastasis in the PyMT model. Also, depleting CD163/RelmA+ Macrophages decreases TGFβ production, which attenuates fibrosis, LOX/PLOD2 expression, collagen crosslinking, and ECM stiffening. They believed that inflammation and myeloid cells brought in ample amounts of TGFβ in the environment, stimulating fibroblast to produce matrix protein and stiffening the environment, which drove tumor invasion. Evidence for that is that there are tons of fibrosis around low-infiltrated tumors. They looked into the phenotype of myeloid cells and found PyMT tumor-associated macrophages become pro-tumorigenic as malignancy progresses and fibrosis/stiffening increases. They prevented crosslinking stiffening of the tumor using LOXi, and all ECM marked by myeloid cells disappeared. RNAseq revealed the upregulated macrophages ECM genes which suggested elevated TGFβ singling. A stiff ECM potentiates TFGβ-dependent ARG1 and UCP2 induction in macrophages. To verify whether ablating TFGβ signaling in the myeloid compartment regulates ECM stiffness-dependent pro-tumor immunity, they implanted tumor cells into TFGβ mutant mice. They found an increase in Arg and Ucp2 expression suggesting a pro-tumor like phenotype in a stiff environment, but it went away in TFGβ KO mice. The pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL1-β were also restored. They also saw a reduction of ECM protein, a decrease in tumor size, and less metastasis. There are innate and adaptive responses. Under normal conditions, the innate immune system function normally, and it helps the adaptive immune system to be anti-tumor. If the innate system was corrupted, it would drive a pro-tumor phenotype. By deleting TFGβ, the innate immune response is corrupted, then the adaptive immune system will respond and allow CD8 cell infiltration. Preventing TFGβ signaling in myeloid cells improved T-cell activation. ECM protein synthesis requires a large amount of proline, up to 40%. It needs lots of glycine and glutamine to make proline. Metabolic flux analysis indicated that a stiff ECM promoted proline synthesis in macrophages. CD8 needs arginine, which can serve as a substrate to synthesize proline. Macrophages interacting with a stiff ECM deplete arginine from the media, compromising T cell activity. Metabolomics revealed a fibrotic/stiff breast tumor stroma that drove metastasis was characterized by depleted levels of arginine. Arginine depletion was not acting alone. It was linked to increased ornithine, which compromises CD8 T cell metabolism. An in vitro co-culture using the OVA model indicated ornithine inhibited CD8 function and viability and tumor cell killing in culture. CD8 cells could kill OVA expression cells efficiently until ornithine was added to the culture. They confirmed this result in vivo, and found that checkpoint inhibitor response was regulated by tumor Arginine and Ornithine metabolites.

In the end, Dr. Weaver summarized this process in the tumor environment that once the myeloid cells are stimulated, they will come in and produce TFGβ1, which contributes to tumor microenvironment stiffening, and that, in turn also change the phenotype of those myeloid cells, they start making ECM proteins, which changes the metabolic environment of those tumors, and CD8 will not be able to survive or proliferate when they come in.

The symposium concluded with an open Q&A discussion section whereby insightful and innovative ideas were shared between the speakers and co-chairs. To enjoy the full playback and open discussion of ‘Mechanobiology’ jointly organized by Science/AAAS and Westlake University, please visit: https://live.vhall.com/v3/lives/watch/166361837

We would like to sincerely thank the three distinguished guest speakers, Dr. Jan Lammerding, Dr. Jody Rosenblatt, and Dr. Valerie M. Weaver, for their time and openness in sharing their latest research and ideas in the field of 'mechanobiology,' as well as co-chairs Dr. Zhenjie Xu and Dr. Stella Hurtley for their expertise and added insights. We would also like to extend our sincere thanks to all audience members who joined live and helped facilitate an informative and engaging symposium shared across the world.

Please check out our previous parts of this symposium series, and we very much look forward to you joining us in our upcoming parts, as we work towards an open and global platform for scientific discussion and innovation.

Science/AAAS and Westlake University Symposium Series

Part 1 | Gene Editing | https://live.vhall.com/v3/lives/watch/925591016

Part 2 | Biomolecular Condensates | https://live.vhall.com/v3/lives/watch/340760384

Part 3 | Protein Engineering | https://live.vhall.com/v3/lives/watch/537973129

Part 4 | Dynamic Molecular Systems | https://live.vhall.com/v3/lives/watch/703086320

Part 5 | New Insights into Host–Virus Interactions | https://live.vhall.com/v3/lives/watch/123859990

Part 6 | Optogenetics | https://live.vhall.com/v3/lives/watch/957350315

Part 7 | Imaging Tissues, Cells and Molecules | https://live.vhall.com/v3/lives/watch/418528741

Part 8 | Mechanobiology: | https://live.vhall.com/v3/lives/watch/166361837