Search websites, locations, and people

ABOUT

ACADEMICS

RESEARCH

ADMISSIONS

NEWS & EVENTS

CAMPUS LIFE

INNOVATION

CAREERS

Researchers Discover that Donut-shaped Mitochondria Lead to Taller Children

14, 2023

Email: zhangchi@westlake.edu.cn

Phone: +86-(0)571-86886861

Office of Public Affairs

Prof. Lianfeng Wu, Prof. Xianjue Ma, and Prof. Jian Yang from the School of Life Sciences at Westlake University recently published an article in the journal of Cell Research entitled "Maternal Aging Increases Offspring Adult Body Size via Transmission of Donut-Shaped Mitochondria". Their study investigated nematodes, fruit flies, and humans, and found that, in all three, the reproductive age of a mother can affect the height and other characteristics of her children even when they reach adulthood. The research team set out to discover the biological mechanism responsible for this phenomenon.

To access the paper, please visit: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41422-023-00854-8

Mothers Are Getting Older

In recent years, rapid economic development and social change have led to an increase in the average age of mothers. The change in the single child policy in China has encouraged many mothers to think about having more children. Longer times spent in education, and the desire to establish a career before having children have also led to many women delaying their first pregnancy. Statistics show that the proportion of older women becoming pregnant in China has increased from 10.1% in 2011 to 19.9% in 2016, with a significant increase of 2% in mothers over 40 years old.

In Shanghai, for example, the average age of first pregnancy rose from 26.6 in 1980 to 30.36 in 2022. This is consistent with the worldwide trend. The average ages for first pregnancies in both the UK and Germany are above 30. How will this trend impact coming generations? What influence does it have on healthy reproduction?

Researchers Focus on Advanced Maternal Age

Is it safe for an older woman to have a baby? How will it affect the child's health? These are constant concerns. It has always been understood that giving birth at an advanced age is physically and psychologically more challenging for mothers, but the impact on the long-term health of children is unclear.

It has long been thought that children born to older mothers are smarter, although whether this is because of biological or environmental factors is a matter of conjecture. However, epidemiological data clearly indicate that there are significant impacts on children's physical health, as pregnancy later in life appears to increase the risk of developmental disorders such as autism and chromosomal disorders such as Down syndrome, among others. Although the statistical evidence for the effects of aging is clear, the biological mechanisms that underlie the trends are still unclear. The phenomenon is generally referred to as the maternal age effect (MAE) and study of the factors involved has become a focus of scientific research.

Children of Older Mothers Become Taller Adults

Wu’s team has been working on metabolism and aging for some time. One of their research interests is the impact that reproductive age has on offspring. They noticed that the offspring of older nematode worms tend to be unusually long, which triggered their curiosity about whether this might also be the case in humans.

Nematodes of the genus Caenorhabditis elegans are commonly used in genetic research. They have two genders: male and hermaphrodite. Researchers usually use hermaphrodite worms in experiments, so there is scant understanding of the gender-related effects of male worms on their offspring.

The team specifically investigated whether the reproductive age of male worms affects the body length of offspring and, somewhat to their surprise, found that the body length of offspring was completely unaffected by the reproductive age of the “father”, but was affected by that of the "mother”.

To explore this phenomenon further and establish whether it occurs in other animals, Wu’s team collaborated with Ma’s and Yang’s teams. Ma is an expert on fruit flies, which he has used for many years to study the relationship between organ size and the molecular mechanisms of cancer. Yang’s expertise is in human genetics, mainly using genetic analysis to study the relationship between complex human traits and diseases. Their joint experiments established that the phenomenon occurs consistently in nematodes, fruit flies, and also in humans. In all three it is the reproductive age of the "mother" – rather than the "father" – that affects the height of the "child". It became clear that this is a manifestation of MAE.

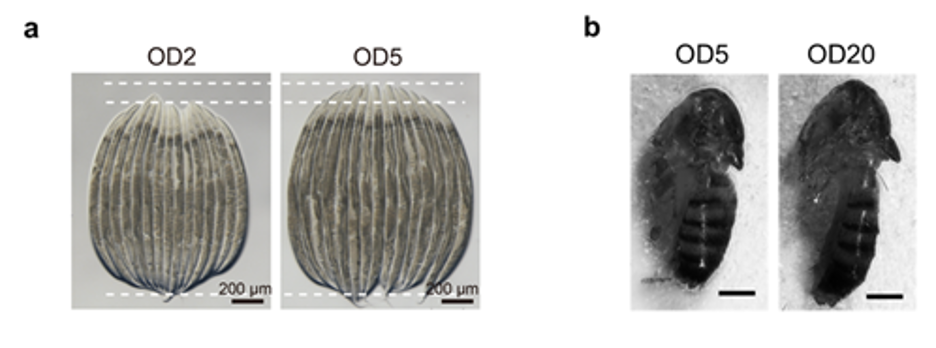

Figure 1: Comparison of size of offspring.

Figure 1: Comparison of size of offspring.

a) Offspring of younger nematode (OD2)

Offspring of older nematode (OD5)

b) Offspring of younger fruit fly (OD5)

Offspring of older fruit fly (OC20)

“Donut” Mitochondria and Child Height

On closely examining the reproductive systems of young and old nematodes under an electron microscope, researchers were surprised to observe many “donut-like” mitochondria in the reproductive systems and embryos of older nematodes. When they tracked the development process of the children of older worms, they found that these unusual mitochondria did not completely disappear until the worms reached sexual maturity. The donut mitochondria then became the focus of their investigation.

Mitochondria are a bit like batteries – they provide the chemical energy that fuels activity in cells. It appears that the donut mitochondria are in a dormant state, probably as a result of external stress. When the stress signal disappears, the mitochondria recover their usual rod shapes and resume their normal functions. There has been relatively little study of donut mitochondria. They were first observed in the retinas of chickens in 1982, where their occurrence was found to increase with age. In 2006, they were also identified in the brainstems of adult rats and, in 2014, they were found in the prefrontal lobes of aged rhesus monkeys’ brains.

In this study, the researchers found that inducing the production of donut mitochondria in "children", even those of younger nematode "mothers", increased their body length. Conversely, editing out the genes responsible for the formation of donut mitochondria, thus preventing their occurrence, prevented the abnormal growth. These twin findings effectively confirm that donut mitochondria play a decisive role in the increased length of the children of older mothers.

Mechanism Behind Donut Mitochondria

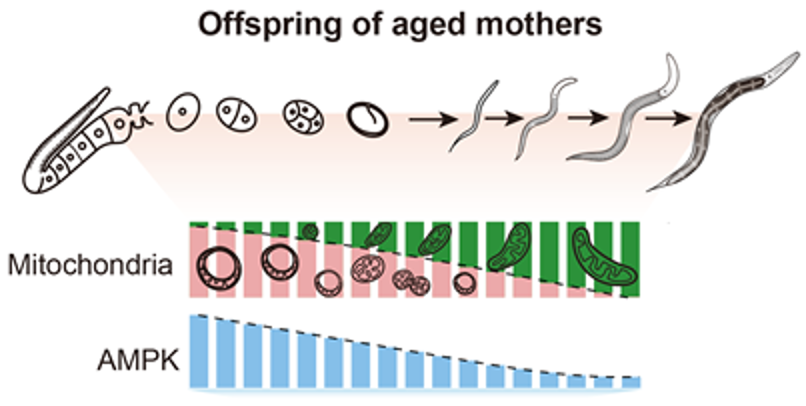

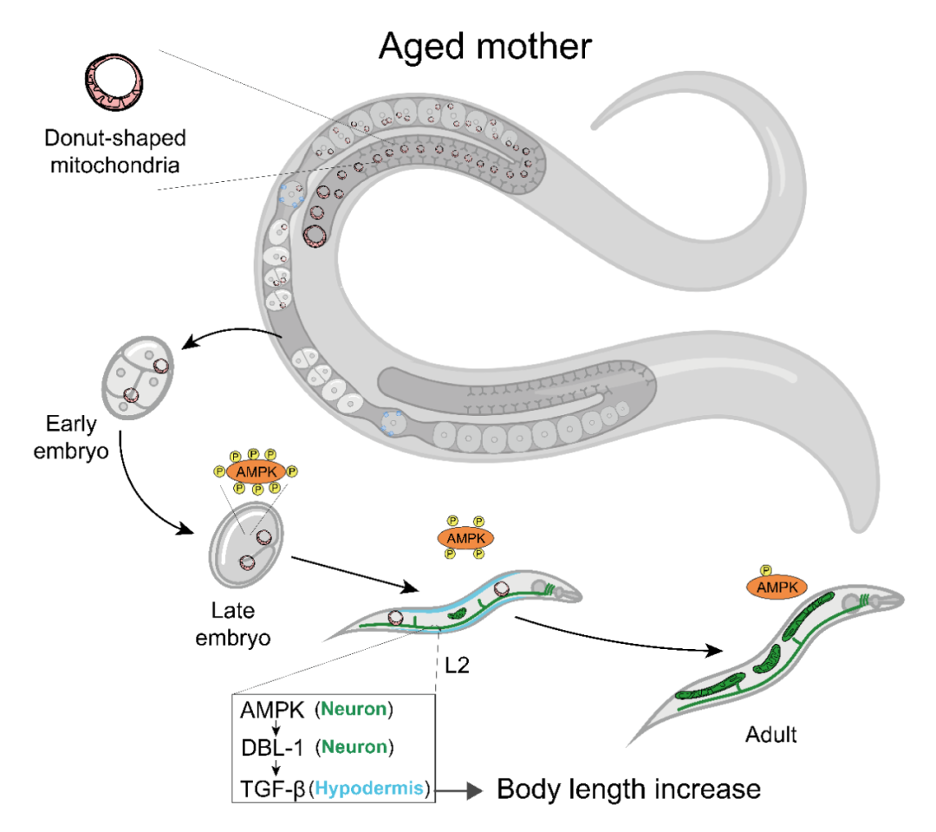

The team went on to investigate the mechanism that causes the mitochondria to fall in and out of the “donut” state. They found a positive relationship between the occurrence of donut mitochondria and levels of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) – an important enzyme that is sensitive to and exerts control over energy levels in cells. When cell energy levels are low, AMPK is activated and begins to stimulate a range of energy-generating processes, including mitochondrial activity.

Test results showed that the offspring of aged worms had high AMPK activation levels from the embryo state all the way to sexual maturity. They also found that size enhancement stops once AMPK is repressed, with the offspring becoming much the same size as other juveniles. This confirmed that donut mitochondria enhance worm growth through AMPK, and that the donut mitochondria and AMPK regulate each other.

The next step was to identify the mechanism by which AMPK activation stimulates enhanced growth. The team observed that there was an apparent correlation between AMPK activation and signaling activity in DBL-1/TGF-β enzyme molecules which, among other functions, influence embryo development. To test whether this was a factor in the MAE, AMPK was artificially activated in a control group. An increase was duly observed in DBL/TGF-β signaling activity. When AMPK activation was suppressed, the opposite occurred, confirming the link between increased AMPK activation levels and growth stimulation driven by DBL/TGF-β signaling.

The team’s diligence and perseverance had revealed how the MAE affects offspring from embryo development all the way to sexual maturity: from their initial observation of the link between age and embryo length, by way of the connection between enhanced growth and the occurrence of donut mitochondria, through identifying the correlation between AMPK activation and the occurrence of donut mitochondria, to finally identifying the relationship between AMPK activation and growth stimulation by signaling along the DBL/TGF-β pathway.

The work of the Westlake team, in revealing the presence of donut mitochondria in the reproductive glands of aged worms and confirming that they can be passed on to offspring as a factor in the MAE, is the first time that the biological functions of donut mitochondria in animals have been reported.

This study explored the long-term influence of the MAE on the size of nematode offspring and succeeded in identifying and explaining the biological mechanism behind it. More research is needed to determine whether the same principle can be applied to other health conditions of MAE-mediated offspring, and whether donut mitochondria could serve as a biological marker for reproductive aging.

Figure 2: Model of mitochondria-AMPK interplay mediating offspring adult size via the MAE.

Figure 2: Model of mitochondria-AMPK interplay mediating offspring adult size via the MAE.

Figure 3: Model of mitochondria-AMPK interplay in mediating offspring adult size via MAE.

Runshuai Zhang, a Ph.D. student of Westlake’s 2020 cohort, Jin’an Fang, research assistant, and Ting Qi, deputy researcher, are the first authors of the paper. Prof. Lianfeng Wu, Prof. Xianjue Ma, and Prof. Jian Yang are the corresponding authors. The project was supported by Prof. Di Chen of Nanjing University and Prof. Dan Yang of Westlake University. It was funded and supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Westlake University, Westlake Laboratory, and the Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Growth Regulation and Transformation Research.