Search websites, locations, and people

ABOUT

ACADEMICS

RESEARCH

ADMISSIONS

NEWS & EVENTS

CAMPUS LIFE

INNOVATION

CAREERS

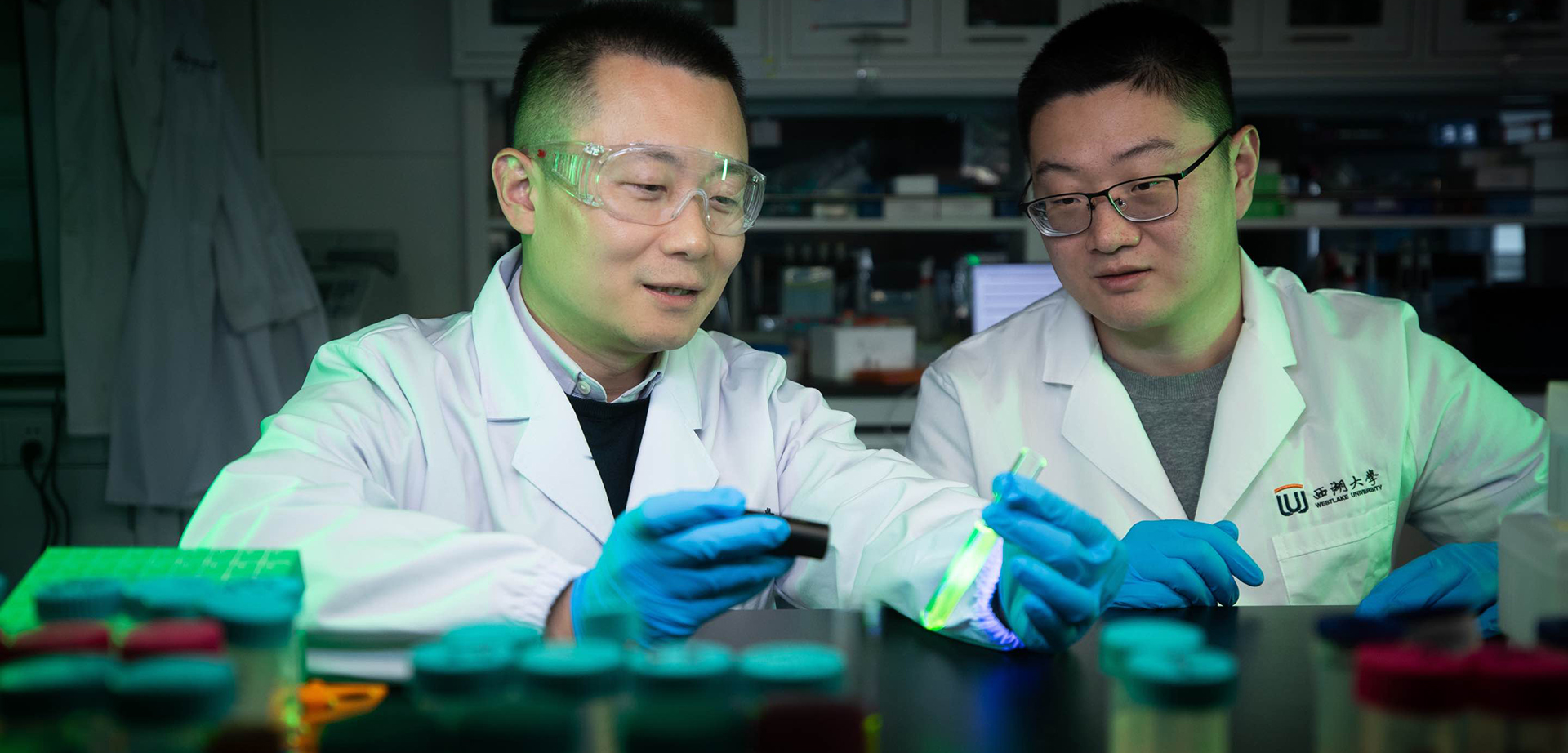

Do "liquid robots" live in cells? Westlake University reveals the secrets of layered membrane-less organelles for the first time

01, 2023

Email: zhangchi@westlake.edu.cn

Phone: +86-(0)571-86886861

Office of Public Affairs

On November 16th, at 16:00 London time, Zhang Xin's team from the College of Science at Westlake University published a paper in Nature Chemical Biology. They systematically revealed the crucial role of micropolarity to control the layered structure of biomolecular condensates using novel environmentally sensitive fluorescent molecules. This work provides a new molecular mechanism for understanding the structures and regulations of membraneless organelles within cells.

In the movie "Terminator," the liquid metal robot T-1000 has no fixed form and can transform into humanoid shapes or even into the floor. Even if it is shattered into pieces, it can reassemble and continue its work. This ability to shatter and reassemble can actually be found in each of us—inside cells, various "components" in a liquid droplet state are involved in complex life activities.

However, the superpower of cells possessing "liquid components" has only been recognized by the scientific community in the past decade.

In 2009, scientists first discovered liquid droplet-like germ granules in C. elegans. These liquid droplet-like substances are membraneless organelles, lacking the traditional "shell" structure (i.e., membrane), and they perform life tasks by forming liquid-like assembly. Some membraneless organelles possess multiple layers, e.g., nucleolus. Interestingly, these layers do not fuse but work cooperatively accomplish important physiological processes within cells.

Taking the nucleolus as an example, it is an membraneless organelle located within the cell nucleus, and exhibits three liquid-like layers—the fibrillar center (FC), the dense fibrillar component (DFC), and the granular component (GC).

Under normal physiological conditions, these three layers do not fuse with each other but work cooperatively to accomplish essential physiological functions such as ribosome synthesis. Previous studies have mainly focused on unraveling the physiological roles of each layer in the nucleolus, while lacking precise answers to the fundamental question of how their layered structures are formed. For instance, why won't these three layers merge with each other? What chemical principles determine which layer stays inside and which one is on the outside?

In this study, they have shifted their focus to the "underlying principle" of membraneless organelles to address the above-mentioned questions, from the perspective of the innate biophysical parameter—polarity.

What is polarity? Simply put, it is related to the distribution of electrical charge over a molecule. The more uneven the distribution of charges, the greater the polarity. For example, water molecule is a typical polar molecule, while most lipid molecules have relatively even charge distribution and belong to nonpolar molecules. Some physical properties of macroscopic substances, such as solubility, melting point, and boiling point, are actually related to the polarity of molecules. The microscopic polarity of membraneless organelles can be seen as the sum of molecular polarities within a local range, representing the unique chemical microenvironment within membraneless organelles.

The team led by Zhang Xin first induced the formation of protein droplets in vitro. Subsequently, they introduced SBD fluorescent molecules into the protein droplets and measured the microscopic polarity of the droplets through fluorescence lifetime imaging. Although these droplets appeared similar in appearance, the fluorescence molecules entering different droplets exhibited significant differences in lifetime, indicating distinct polarities of these droplets.

Next, the research team mixed various protein droplets pairwise, totaling 15 groups, to further investigate the relationship between droplet structures and polarity. Under the microscope, it was observed that the mixed droplets formed complex miscibility, with some cases completely miscible and others forming layered structures. Further research on the layered droplets revealed a the critical role of polarity: the difference in polarity between different protein droplets determined whether they would form layered structures, and the relative magnitude of the protein droplet polarity determined their relative positions in the layered structure. These findings provide important physicochemical insights into the structures of multi-layered biomolecular condensates.

After testing in model proteins, the research team further validated whether polarity controls the layered structure of membrane-less organelles in animal cells. They transfected and expressed key proteins of the nucleolus and selectively labeled different layered structures of the nucleolus with an improved SBD probe.

These experiments in cells similarly revealed that polarity determines the relative arrangement of layered membrane-less organelles.

The research team led by Zhang Xin has, for the first time, revealed the decisive role of polarity in controlling the layered phenomenon of membrane-less organelles. The identified chemical principles provide a direct theoretical basis for understanding and intervening in the regulation of layered membrane-less organelles within the body. The unique microenvironment within membrane-less organelles has a crucial impact on their biological functions, and abnormalities in their microenvironment have been implicated in various neurodegenerative diseases and cancer. Therefore, targeting membrane-less organelles and modulating their microenvironment are important directions for drug development in related fields.

Furthermore, the experimental method developed by Zhang Xin's team in this study, which combines fluorescence lifetime imaging with environment-sensitive fluorescent probes, can not only be used for measuring the properties of the microenvironment within membrane-less organelles but also extended to other cellular spaces, thereby expanding the quantitative characterization of microenvironments to a broader range of life science research.

RELATED